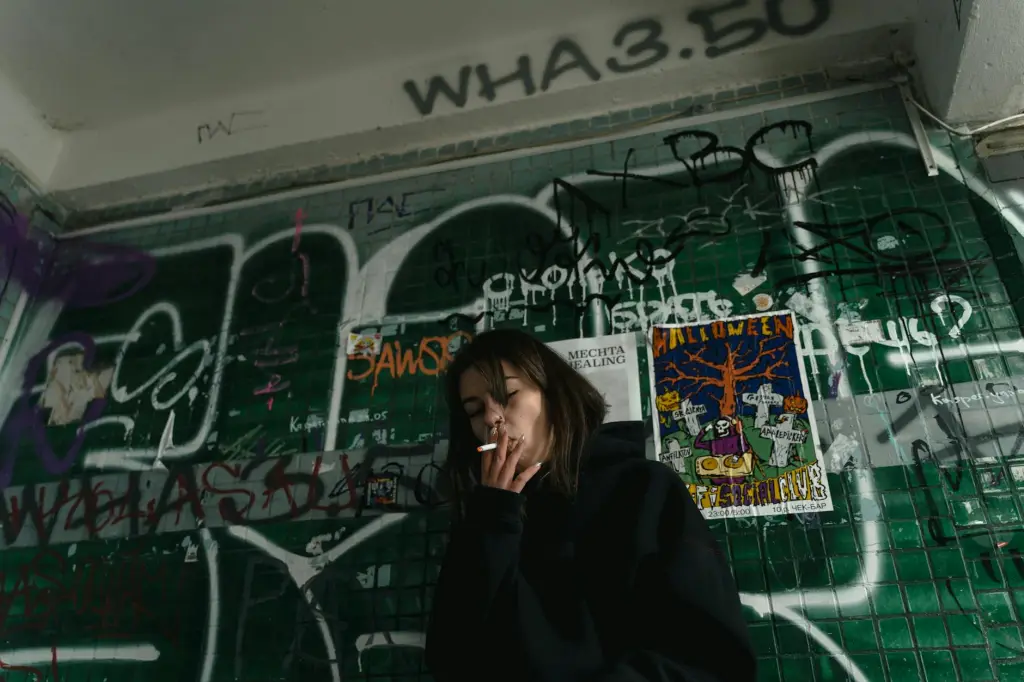

What does it mean to love someone who is struggling to connect? How do we cope when the depth of care we feel cannot be received by our loved one? These are certainly ambiguous questions. And yet, if we have someone close to our hearts struggling with a substance use disorder, these questions can feel like an open wound. The pain of unrequited love is often portrayed in the heartbreak of romantic relationships, the death of loved ones, and in the inevitable transitions of our lives. It is difficult to conceptualize unrequited love as something experienced by those of us who care for parents, romantic partners, children, siblings, and friends struggling with substance use. Loving an addict leaves us breathless. Loving an addict makes us wonder where it all went wrong: how we may or may not have caused this dependency, how our absence or presence may have swayed the outcome. Loving an addict makes us wonder how we can know someone to their bones, only to find ourselves speaking to a shell of the person we once knew. The pain of living death, meaning the loss of a connection we once understood, characterizes substance use dependency and cannot be adequately described in words.

Those struggling with substance use undergo immense amounts of pain and suffering. Dependency on a substance is a call for help in and of itself, whether conscious on the user’s part or not. When we are fulfilled, we do not seek ways to numb that feeling. When we are capable of giving and receiving love, we are more interested in feeling our natural endorphins than a fabricated version of the real thing. The purpose of this writing is not to undermine the intense shame, grief, and suffering of those with a substance use dependency. It is simply written to express empathy for the loving witness to this suffering, namely individuals closest to the wreckage that is substance use dependency. The more we love, the closer we get. The closer we get without wisdom and aid, the more tendencies we have to twist ourselves into what we believe our loved one needs. We come by this genuinely, with the greatest intent, and it transports us to further internal suffering. Many of us end up carving out parts of ourselves because the pain of bearing witness to addiction proves too intense. We hope giving all of ourselves will bring back the loved one we once knew. As a result, two people develop a dependency. One on the substance, and the other on the resulting chaos.

Codependency is a word that gets thrown around often in support groups for loved ones of addicts. It is a term that used to annoy me, largely because it reigned true within relationship dynamics I held between my brothers. They were entirely dependent on their substances of choice, and I was entirely dependent on the cycles of chaos that ensued. It is easy to ridicule ourselves upon the realization that we have become codependent with the ups and downs of our loved ones substance use. It is harder, and even still, more productive to have empathy towards ourselves: this is what opens pathways for transformation within our long, well constructed coping mechanisms.

There are a multitude of options to explore support when we are brave enough to admit our loved ones dependency is beyond us. Some find avenues like AlAnon, a group for loved ones of alcoholics, to be helpful in cultivating self-compassion and community surrounding addiction. Others prefer a more solitary approach, in which texts including Codependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for Yourself can provide solace for individuals Loving Through Addiction wondering where to begin healing attachment to their loved ones actions. Codependent No More reads, “If I make one point in this book, I hope it is that the surest way to make ourselves crazy is to get involved in other people’s business, and the quickest way to become sane and happy is to tend to our own affairs.” The first time I read this quote, it provoked feelings of anger, helplessness, and an internal echo which screamed “How the hell can I help without paying attention to them?! Who else will take care of them?” The blatant nature of this quote, while intense, gives us an opportunity to see how caring for ourselves is an act of community care. After all, we are most wounded by our loved ones inability to see their own worth within substance use dependency. Somewhere along the process, through the blind grief and pain, we lose our own worth while chasing theirs. Some find individual therapy most beneficial, where our painful realities have the chance to be held vulnerably and compassionately. I have chosen, and continue to choose, a combination of these options to begin finding my inner voice within the numbing experience of my brother’s substance use dependencies.

My youngest brother has beautiful, big brown eyes. He plays the fiddle as if he was born with it. He speaks fluent Spanish because he loves to engage with others, and will learn to understand them if he cannot. He first used intravenous methamphetamine when he was nineteen. My eldest brother has my initials tattooed on his arm. He wrote me so many letters that I have a box full of them. He is witty and perceptive. His first felony came from a charge for heroin distribution, a decision he made to afford his own fix. Both of my brothers called me to wish me a happy birthday this year. If we can practice holding their humanity alongside our undeniable grief, if we can balance their right to navigate their lives with our defiant “No!!”, our nature of loving changes. Loving means we hold compassion for everyone involved. Loving means we do not interfere with another being’s capacity to choose. Loving means we practice connection to ourselves within the chaos. Loving means releasing the outcomes of substance use dependency long out of our control. Loving, at its core, permeates everything, takes nothing, and exists within the complexity of an unbreakable bond.

References

Beattie, M. (1992). Codependent no more : how to stop controlling others and start caring for yourself. Taylor & Francis.